Boy, did they trim them.

The heat of the summer is actually a good time to trim live oaks if one wants to minimize the spread of oak wilt disease. But any benefit derived from this was quickly negated by the fact that well over 25% (more like 50% to 75%) of the canopy was trimmed from these trees in record heat and dryness. Why were these trees trimmed so harshly? It was in the “agreement.”

The “agreement,” to which I am referring was signed four years ago by a group of interested neighbors and Austin Energy. At that time, due to more stringent federal rules that had recently been enacted concerning the distance tree limbs could be from existing high-tension lines, Austin Energy proposed cutting down all seven of the large oaks that grow in the greenbelt from the edge of Swearingen Drive running down to the west toward the creek. After a prolonged negotiation, it was decided that the oaks would be spared, but trimmed every four years to standards set by Austin Energy.

As it turns out, Austin Energy still wants to cut down the seven live oaks for the same reason that they wanted to four years ago. The decision on whether to cut down the trees or not was never actually made, it was merely kicked down the road for four more years. The four years is now up, and Austin Energy still wants to cut down the oaks. On Monday night, October 5, 2009, at a special meeting of the Gracy Woods Neighborhood Association, it was voted to APPROVE (by a final vote of 14 to 11) the removal of these seven oaks contingent upon approval of the mitigation offered by Austin Energy. I have volunteered to be on the committee that reviews the mitigation.

What is this mitigation? The details have not been decided yet, but it is basically the same kind of mitigation that was done at the Tallowfield end of the greenbelt four years ago when the large trees were cut down from under the power lines there. A number of small, relatively short-lived native (well, mostly native) trees, along with irrigation, were installed.

It should come as no surprise to anyone who has read this blog that I am opposed to the cutting down of large oaks. First and foremost, these oaks provide shade all year around in our greenbelt. The small trees on Tallowfield provide little shade, and none in the winter. Large, established live oaks have the advantage of requiring no irrigation, even in a severe drought, in exchange for year-around shade.

The ages of these Swearingen oaks, when totaled, easily exceed 1,000 years, but that figure does not begin to tell the whole story. The hillside on which they grow is a dry, rocky hillside with little soil. In the past thousand years, thousands and thousands of oaks have attempted to grow on this hillside – oaks of genetically hardy and locally adapted heritage. Of those many thousands of oaks, seven have made it to maturity. The rest were either genetically too weak to survive (this includes tolerance of heat and cold, drought, attacks by pests and pathogens, etc.), germinated in the wrong place to establish a good root system, or were otherwise just plain unlucky. The seven that now stand are the strongest of thousands. There is simply no way that humans can replace them. There is also now no more recruitment of new oaks. The natural process of selecting the strongest to survive has been halted. The constant mowing and other heavy use demanded by our growing human population means there will be no more recruitment of oaks. These oaks are the last.

Gracy Woods is losing its oaks. We have oak wilt in the neighborhood, which is in the process of killing many of our oaks. A number of large oaks were cut down when the new housing development was put in just south and east along Swearingen Drive, around the original Gracy farmhouse. There are also well over 500 live oaks of all sizes on the property about to be developed for a medical facility at the corner of Parkfield and Braker Lane. The preliminary plans that I have seen call for the removal of many of these oaks.

There is no doubt about it – the number of live oaks in Gracy Woods is declining.

Live oaks are excellent for wildlife. Many birds roost in live oaks all year around because the evergreen foliage is good protection from both excessive heat, cold, and all kinds of precipitation. Oaks protect early spring nesting species from our occasional violent storms. Also in the spring, when the new live oak leaves attract lots of moth caterpillars that hang down from the canopy on their long web-like strands of silk, the spring bird migration comes through. Particularly for the most beautiful and fragile of all our spring migrants, the wood warblers (please see my earlier post), these caterpillars help fuel the long journey north. Fewer oaks mean fewer caterpillars, which mean fewer warblers flying through our neighborhood. I find that tragic news, indeed.

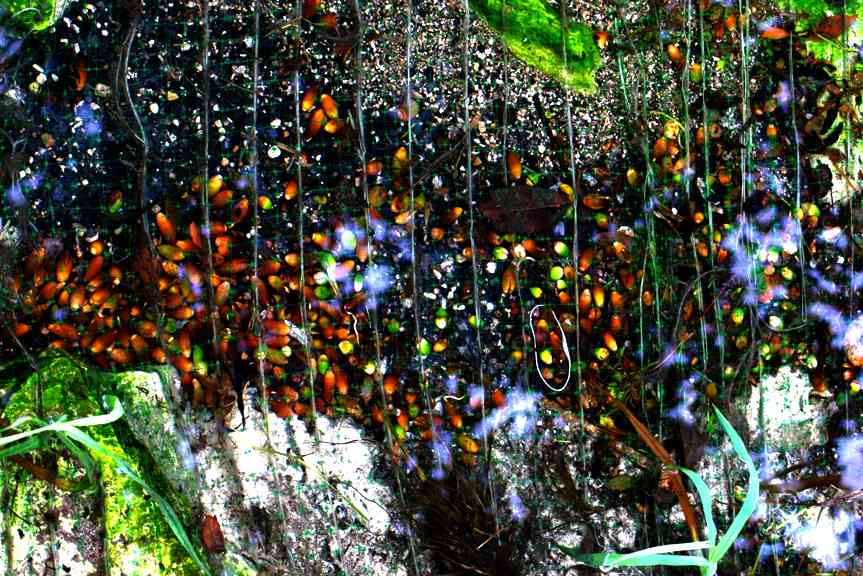

And don’t forget the acorns - lots and lots of acorns! This fall bonanza provides food for all kinds of wildlife, including some you wouldn’t normally think about. Below is a picture of one of our creeks after a recent rainstorm, filled with acorns that also feed an aquatic chain of life.

So why would Austin Energy want to cut these oaks down? At the end of the day, I believe that it's all about money. The City of Austin used to have its own tree crews, but those crews have been cut back. Most tree-trimming is now contracted out, which is only cost-effective if it is not done too often. Austin Energy wants to trim the greenbelt only once every four years. In order to keep the trees from growing too close to the high tension lines in four years, according to the Austin Energy arborist, the cutting needs to be extreme, as demonstrated by their recent actions. And sooner or later, with such extreme cutting, the oaks may die. So we might as well cut them down now, and Austin Energy will pay for the mitigation, or so the logic goes.

Is this a self-fulfilling prophecy?

I believe that the oaks could be trimmed more often (say, once every one or two years) and not as harshly, in which case they would certainly look much better. They could be permitted to grow a little taller, and continue to shade the greenbelt, providing habitat for wildlife. But Austin Energy will not grant us that option because it is too expensive.

Our neighborhood is being offered two options as a one-time deal: A planting of smaller trees (with irrigation) in exchange for our support for the cutting of the seven oaks, or continued extreme trimming once every four years. If we choose the latter, there will be no mitigation offered again if the oaks do not survive this kind of trimming. One of the aspects about this agreement that worries me is that once the installation is completed, Austin Energy turns the landscape management over to the Austin Parks and Recreation Department (PARD). Austin Energy is a profitable enterprise; PARD is the one city department that most frequently seems to have its budget cut. Neither of these options sounds like a good deal to me.

There is a principle I learned years ago in college: Think globally and act locally. Globally, rising carbon dioxide levels threaten our weather patterns. At least 20% of rising carbon dioxide levels is caused by deforestation. Large trees absorb carbon dioxide, store it in their trunks as a component of wood for as long as they stand, and release oxygen and water as a result of the process of photosynthesis. This process also helps forest canopies reduce heat, even in city environments. Partly as a result of climate change and partly as a result of habitat loss, over one quarter of all bird species are in decline, including many warblers. So if we are to think globally and act locally, it seems to me that we should be willing to put a little time, energy, and money into trying to save the seven Swearingen oaks instead of cutting them down.

What do you think?

Update: for now, the seven oaks of Swearingen Drive will remain standing, because the special committee appointed by the GWNA to decide whether to approve the proposed mitigation plan or not did not approve of the plan. Going forward, however, the GWNA would like to come up with a more desireable alternative to the serious trimming that these oaks currently endure every four years, so we have set up a new committee to search for a more lasting solution. Please feel free to provide your input!